Cogito Blog

What did the “Comcast Agent” really do wrong? (And could Cogito Dialog have helped him?)

Anyone who has tried to cancel a service over the phone knows how difficult this type of conversation can be. Such phone calls often drag on longer than desired, filled with pointed and demanding questions. Customers have come to expect a potentially tense conversation; however, the recently viral “Comcast Call” may have been one of the least successful interactions recorded and shared, ever.

For those who haven’t heard it, the Comcast Call is a conversation between a Comcast agent and a customer who wants to cancel his service. The agent aggressively pushes back on the customer’s request to cancel. His behavior has been described across the internet as belligerent, defensive, and rude. Yet, Comcast COO Dave Watson’s response to the recording notes that the agent followed many of the training guidelines put in place for these agents. So, how did the call go so awry in the gap between training and practice? What did the agent really do wrong?

Here’s a recording of the call, if you’d like to hear it:

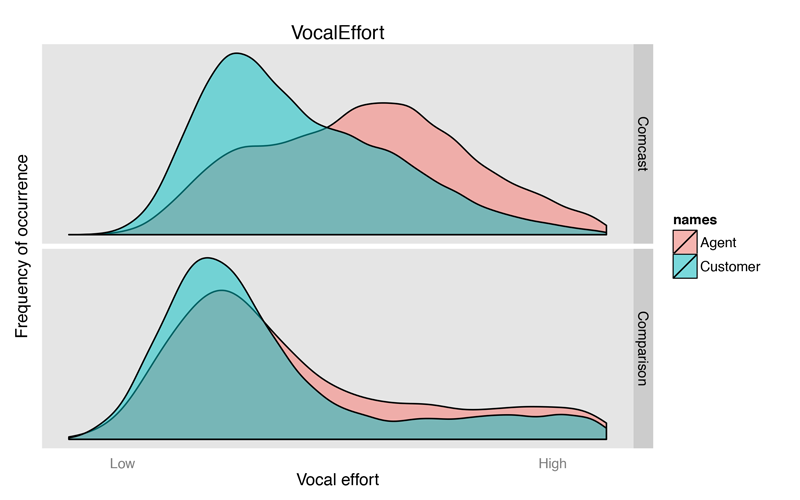

INVESTIGATING VOCAL EFFORT

Vocal Effort is an algorithm that we have recently developed here at Cogito and a tool that applies well to these situations. Vocal Effort provides a means of discriminating soft, quiet voices from loud, tense ones. The algorithm is particularly effective for analyzing telephone conversations because it does not rely on the volume or energy of a recorded audio signal – measures that can be affected by how closely a caller holds a handset to their mouth. Instead, Vocal Effort focuses on the frequency components of speech that are independent of volume or energy. In the below figure, distributions of Vocal Effort are plotted for agents in red and customers in green. During the Comcast call (top panel) the analysis indicates significantly higher vocal effort and an overall tenser voice for the agent, as compared to the customer.

For one of our typical “good” calls (bottom panel), the agent and customer are both highly similar in terms of their vocal effort. Also, both speakers in the “good” conversation display a vocal effort profile that matches the customer in the Comcast call, who was generally perceived as remaining quite calm during the conversation.

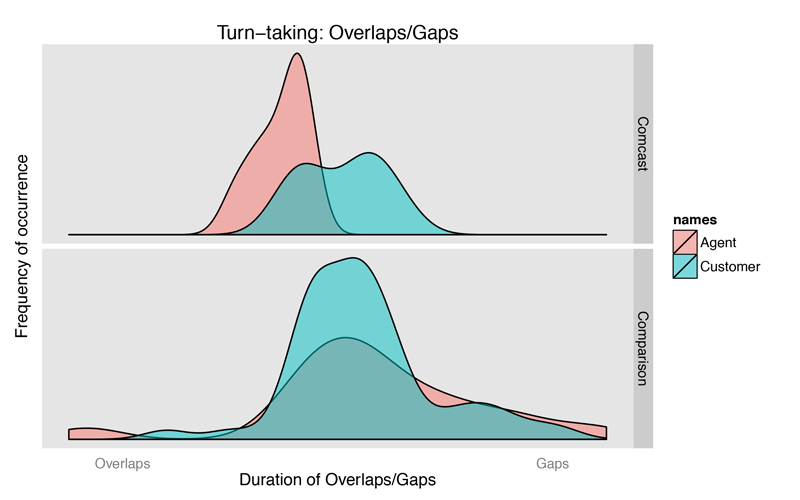

INVESTIGATING TURN-TAKING BEHAVIOR

An important aspect of speaking behavior is turn-taking. It is especially important to measure when we begin to start speaking relative to the person we are speaking to. Allowing too much of a gap or silence, after our speaking partner stops talking can make us seem disinterested; however, consistently leaving too short a gap or overlapping the end of our partner’s speech by too much can be perceived as rude.

In the below figure, distributions pushing to the right indicate a tendency for the speaker taking the turn to leave a gap before speaking, as is shown by the Comcast customer. Distributions pushing to the left indicate a tendency for short gaps or even overlaps, as is shown by the Comcast agent.

In the Comcast call (top panel) the agent (in red) clearly shows a preference for aggressively ‘taking the turn’ by overlapping the customer’s speech considerably. The customer, on the other hand, displays more varied and natural behavior with a greater balance between overlaps and leaving a gap when taking the turn. In our typical “good” call, the customer and agent again display much more similar turn-taking behavior to each other, with widely varying but almost completely overlapping distributions.

COULD THE AGENT HAVE CORRECTED HIS BEHAVIOR IF HE HAD RECEIVED REAL TIME FEEDBACK?

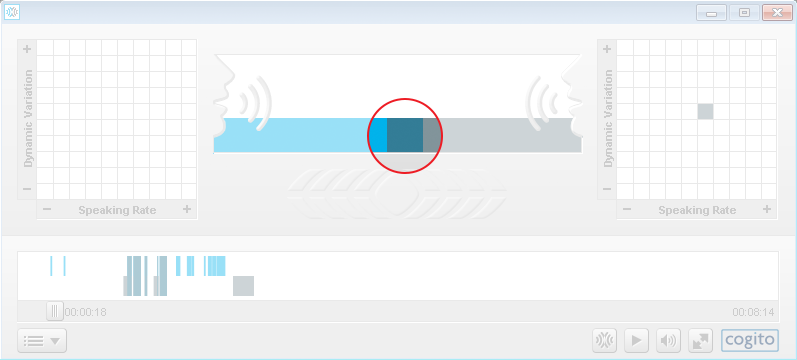

The non-verbal aspects of the interaction, as described above, highlight the lack of success in this conversation. The agent consistently overlapped-over and cut-in on the customer’s speech, and combined this with an overall raised and tense voice. Cogito Dialog provides an effective means for objectively characterizing such behavior, automatically and in real-time.

In this screenshot of Dialog you can see that even a mere 18 seconds into the recording, there is a very high amount of conversational overlap. This means that the agent and customer are speaking over each other at the same time and the conversation is not flowing smoothly.

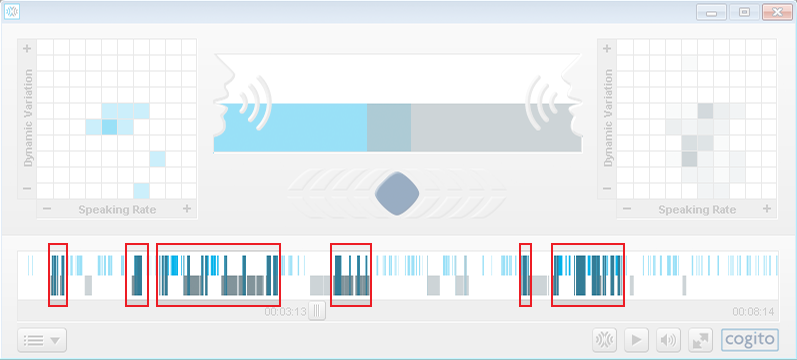

You can see that this behavior continues throughout the conversation. In fact the agent rarely pauses or takes the time to listen. As a result the customer isn’t being heard. Had the agent noticed and modified his behavior at any of these moments, there might been a better outcome to the call.

Could Cogito Dialog have alerted the Comcast agent or his supervisor that the conversation was not building engagement and rapport as desired – that, in fact, the call was creating more distress than it was alleviating? We think so! This looks to us like a very unfortunate public event that could have been avoided.